When comparing porcelain vs sandstone in Cheshire, this is what actually matters. Both are widely available, both look impressive in supplier catalogues, and both appear at vaguely similar price points — until installation costs are included. The practical differences between them, however, are significant, and in Cheshire’s specific conditions — clay-heavy ground and persistent North West rainfall — those differences matter more than they would in a drier, sandier part of the country.

This page gives a direct comparison of both materials across the factors that determine long-term satisfaction: installation specification, drainage behaviour, maintenance demands, realistic costs, and durability in Cheshire’s climate. Neither material is universally superior. The right choice depends on the property, the garden context, and what the homeowner is genuinely willing to maintain over the years ahead.

For full coverage of sub-base specification, drainage design, and patio installation across all materials, see our Patio & Paving in Cheshire guide.

Porcelain vs sandstone in Cheshire, this is what actually matters.

The North West receives some of the highest annual rainfall in England. Cheshire gardens also sit predominantly on clay, which drains slowly and moves seasonally — shrinking in dry summers, swelling after autumn and winter rain. Any patio material laid here needs to cope with both constant moisture and the ground movement that clay creates.

Porcelain in Wet and Frost Conditions

Porcelain is manufactured at very high temperature, producing a dense, vitrified material with water absorption typically below 0.5%. In practice, this means water cannot penetrate the slab in any meaningful quantity. There is nothing to freeze and expand within the material itself, making correctly specified porcelain genuinely frost-proof across Cheshire winters. Algae and moss have little to grip on a dry, non-porous surface — growth is slower to establish and easier to remove than on stone.

Slip resistance on exterior porcelain is determined by the surface texture applied during manufacture. Look for an R11 rating or above for outdoor use in Cheshire conditions. This is a specified, testable property — not a marketing claim — and should be confirmed with the supplier before purchase. Smooth-finish porcelain, designed for indoor use, is not appropriate for a Cheshire garden patio.

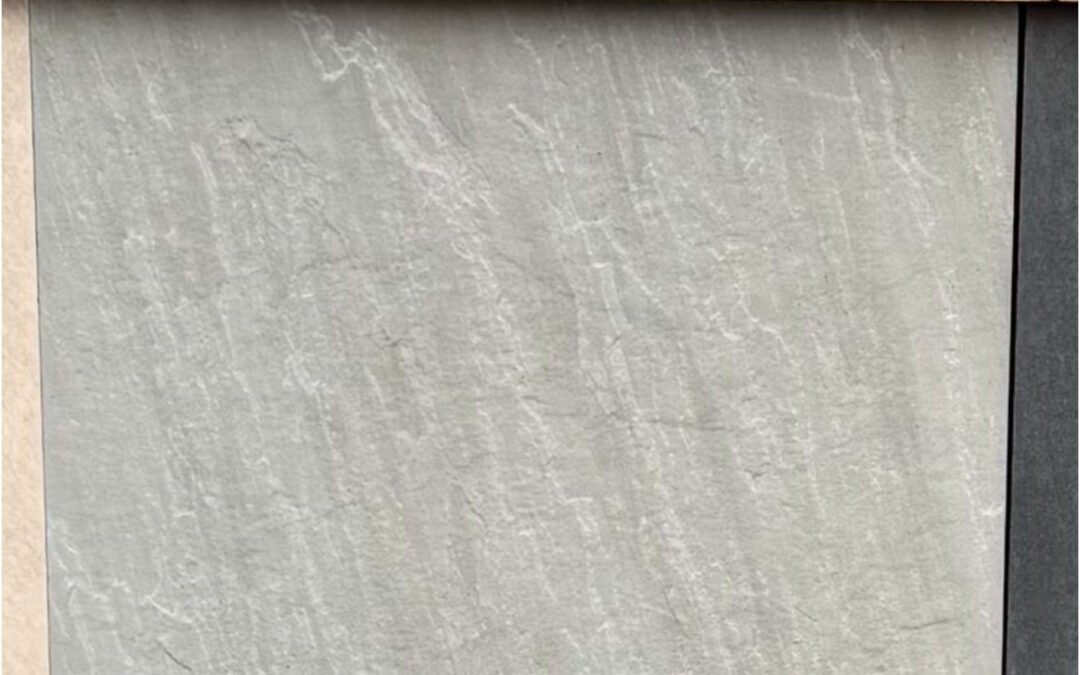

Indian Sandstone in Wet and Frost Conditions

Indian sandstone is a naturally porous sedimentary stone. Water absorption varies significantly by source, grade, and finish — riven surfaces are more open than honed or sawn faces — but all sandstone takes up moisture to a degree that porcelain does not. In Cheshire’s climate, this creates two practical risks: freeze-thaw damage when absorbed moisture expands during frost, and persistent algae and moss in shaded or north-facing gardens where the stone stays damp for extended periods.

Quality, correctly sealed sandstone manages these risks considerably better than low-grade material. Dense, well-quarried Indian sandstone from a reputable supplier — sealed on installation and maintained — performs reliably in North West conditions. The difference in performance between premium and budget sandstone is material, and it is rarely reflected in the initial price comparison homeowners make between materials.

Riven sandstone surfaces provide natural grip in wet conditions. An unsealed or algae-covered sandstone surface, however, becomes genuinely hazardous — arguably more so than a clean, textured porcelain surface.

Installation Specification: Where the Real Differences Lie

Both materials can be installed to a high standard. The specifications are different, and the consequences of cutting corners are different. Understanding these differences helps homeowners evaluate quotes accurately and ask the right questions before work begins.

Sub-Base Requirements on Cheshire Clay

Both porcelain and Indian sandstone require the same sub-base engineering on Cheshire’s clay soils: 150–200mm of compacted granular material (MOT Type 1), laid in 75mm layers with a vibrating plate compactor, over a firm bearing stratum with all soft clay removed. This specification is determined by the ground conditions, not the surface material. Anyone quoting a shallower sub-base on a clay site is reducing the specification regardless of which material they propose to lay on top.

Drainage falls — a gradient of 1:80 to 1:100 away from the house — must be established at sub-base level and maintained through to the finished surface. The finished surface must sit at least 150mm below the building’s damp proof course. These requirements apply equally to both materials.

Bedding and Priming: Where Porcelain Demands More

This is the most significant practical installation difference between the two materials, and the one most likely to be underspecified on cheaper quotes.

Indian sandstone is porous. It bonds to a traditional 4:1 sharp sand and cement mortar bed by absorbing water from the mortar mix during setting. This is a reliable mechanism, well understood, and has been used successfully for decades. Full bed laying — not spot bedding — is still the correct approach to avoid voids and rocking slabs, but sandstone is relatively forgiving of minor imperfections in the bed.

Porcelain is non-porous. It cannot absorb water from the mortar bed, which means the traditional bonding mechanism does not work reliably. Without additional preparation, porcelain laid on standard mortar will de-bond — the slab separates from the bed, producing rocking, hollow-sounding tiles that eventually crack or lift entirely.

The solution, specified by manufacturers including Bradstone and Marshalls, is a slurry primer applied to the underside of each slab immediately before laying. The primer must go onto a clean, dust-free surface — any contamination weakens the bond at exactly the point where it needs to hold. The primer creates the adhesion layer that porcelain’s smooth underside cannot provide on its own. Combined with a full mortar bed — or a flexible adhesive bed on premium installations — this produces a reliable, durable result. Without it, de-bonding is a question of when, not if. For detailed installation guidance, see Bradstone’s guide to laying porcelain slabs.

Jointing also differs. Porcelain expands slightly with temperature variation. Rigid sand-and-cement joints crack as the material moves. The correct specification for porcelain is a polymeric or brush-in flexible jointing compound, and movement joints should be incorporated at intervals and at any abutment with the house wall. Sandstone is more tolerant of traditional mortar joints, though these still require sound sub-base compaction to avoid cracking from ground movement.

Cutting porcelain requires specialist diamond-blade equipment. The material is hard and unforgiving of amateur technique — chipped edges and overcuts are common DIY failures. A skilled installer using the right equipment produces clean, accurate cuts. This requirement contributes to the labour cost differential between the two materials.

Maintenance Comparison

| Factor | Porcelain | Indian Sandstone |

|---|---|---|

| Sealing required | No. Low porosity means sealing provides no meaningful benefit and film-forming sealers can reduce slip resistance. | Yes. Initial sealing on installation and re-sealing every 2–3 years to resist staining, moisture, and algae. |

| Algae and moss | Slow to establish; removed easily with pressure wash and mild detergent. | More prone to growth, particularly in shade; requires regular treatment and cleaning to manage. |

| Stain resistance | High. Food, grease, and organic matter do not penetrate the surface. | Moderate to low without sealing. Quality sealed sandstone resists most common stains. |

| Routine cleaning | Brush and wash. Annual pressure wash sufficient for most Cheshire gardens. | More regular cleaning needed, particularly in damp or shaded positions. |

| Colour retention | Stable. UV-resistant; does not bleach or fade significantly over time. | Can fade, particularly lighter sandstones; periodic re-sealing helps retain appearance. |

| Frost resistance | Inherently frost-proof. No water absorption means no internal freeze-thaw damage. | Quality dense sandstone performs well when sealed. Budget or soft sandstone susceptible to spalling in freeze-thaw. |

| Ongoing cost | Low. Minimal consumables or contractor involvement beyond cleaning. | Higher. Sealing products, professional re-sealing, and more frequent cleaning represent a real ongoing cost. |

Realistic Cost Comparison for Cheshire Projects

Material Costs

Indian sandstone supply-only typically runs from £20–£35 per square metre for mid-range material, with premium dense sandstones towards £45 per square metre. Outdoor porcelain runs from approximately £35–£60 per square metre at mid-range, with premium Italian and large-format collections at £80 per square metre and above.

The material cost gap is real. On a typical 40m² Cheshire patio, the difference in materials alone between mid-range sandstone and mid-range porcelain might be £600–£1,000. This figure needs to be assessed alongside installation and lifetime costs, not in isolation.

Installed Costs

Porcelain installation costs more per square metre than sandstone. Primer, specialist cutting equipment, flexible jointing compound, and the greater precision required in laying all add to the labour cost. Quality patio installation in Cheshire — including full clay sub-base engineering, drainage provision, and skilled laying — typically runs in the region of £150–£200 per square metre installed for porcelain, with sandstone somewhat lower depending on specification.

Groundworks and drainage are the dominant cost driver on both materials. The sub-base specification for Cheshire clay, waste removal, and drainage provision adds substantially to the installed cost regardless of which surface is chosen. A quote that reduces the sub-base specification or omits drainage to lower the headline price is not a saving — it is a deferred problem.

Lifetime Cost

Sandstone’s ongoing maintenance costs — sealing products, professional cleaning, and occasional re-sealing — are real expenditure that accumulates over years. For a 30m² patio, sealing every two to three years represents a consistent running cost. Porcelain’s maintenance costs are negligible by comparison. Over a 15–20 year period, this difference can close or eliminate the initial material cost gap, making porcelain the lower total-cost option for many Cheshire homeowners despite its higher upfront price.

Which Material Is Best for Your Garden

Choose Porcelain When:

- The garden design is contemporary or the property is a modern build

- The patio is south or west-facing and likely to be heavily used

- The garden has shaded areas where algae growth on stone would be a persistent issue

- Maintenance time is limited and a low-effort surface is a genuine priority

- Children or elderly family members use the space and consistent slip performance matters

- A uniform, consistent appearance is preferred over natural variation

Choose Indian Sandstone When:

- The property is period, traditional, or rural — a farmhouse, cottage, or older Cheshire village home — where sandstone integrates more naturally into the architecture

- The natural colour variation and character of real stone is preferred over a manufactured aesthetic

- Budget is a significant constraint and a quality sandstone specification is more achievable than quality porcelain

- Dense, premium-grade sandstone from a reputable supplier is specified — not the cheapest available

Neither material is the right answer in every situation. What matters more than the surface choice is that whichever material is selected, the installation beneath it meets the specification required for Cheshire’s ground conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is porcelain or sandstone better for a Cheshire patio?

In Cheshire’s wet climate and clay-heavy soils, porcelain has practical advantages: it requires no sealing, resists frost and algae more effectively, and is easier to maintain over time. Indian sandstone is the better choice for period properties where natural stone suits the architecture, or where its lower material cost makes a quality installation more achievable. The ground engineering required is the same for both materials — the surface choice is secondary to getting the sub-base and drainage right.

Is porcelain paving slippery when wet?

Exterior-grade porcelain with an R11 slip resistance rating or above is not inherently slippery in wet conditions. The R11 rating reflects a tested, standardised measurement of grip on a textured surface. Not all porcelain carries this rating — smooth indoor porcelain is genuinely hazardous outdoors when wet — so the slip rating should be confirmed with the supplier before purchase. A neglected, algae-covered sandstone surface is arguably more hazardous than clean textured porcelain.

Does sandstone paving need sealing in Cheshire?

Yes. Indian sandstone should be sealed on installation and re-sealed approximately every two to three years, depending on exposure and the stone’s density. In Cheshire’s wet climate, unsealed sandstone absorbs moisture, supports algae and moss growth more readily, and is more susceptible to staining and frost damage over time. Sealing is not optional maintenance on sandstone — it is part of the material’s performance specification. Quality dense sandstone sealed correctly performs well; low-grade unsealed sandstone deteriorates quickly in North West conditions.

Why does porcelain need a primer and sandstone doesn’t?

Sandstone is porous and absorbs water from the mortar bed during setting, which is the primary bonding mechanism in traditional paving installation. Porcelain is non-porous and cannot absorb the mortar in this way, which means the standard bonding mechanism does not function reliably. A slurry primer applied to the clean, dust-free underside of each porcelain slab — as specified by manufacturers including Bradstone and Marshalls — provides the adhesion layer that allows the mortar bed to hold the slab securely. Omitting the primer is the most common cause of porcelain de-bonding and rocking slabs.

Which lasts longer — porcelain or sandstone?

Both materials can last 25–30 years or more when correctly installed and maintained. Porcelain’s durability advantage lies in its inherent resistance to moisture and frost without requiring ongoing maintenance. Sandstone’s longevity depends significantly on the stone’s quality and whether sealing is maintained consistently. On clay ground with Cheshire’s rainfall, a correctly specified porcelain installation is less vulnerable to the conditions that cause premature failure. An under-specified installation of either material — insufficient sub-base on clay, inadequate drainage — will fail regardless of what is on the surface.

Is it worth paying more for porcelain over sandstone in Cheshire?

For most Cheshire homeowners prioritising low maintenance and long-term performance in a wet climate, yes. The higher upfront material and installation cost is partially offset over time by the elimination of sealing costs and less frequent cleaning. For period properties where sandstone is architecturally appropriate, or where budget constraints make a quality sandstone installation more realistic than a quality porcelain one, sandstone remains a sound choice. The worst outcome in either case is a poorly specified installation — under-built on clay ground or inadequately drained — regardless of which surface material is chosen.

For full specification detail on sub-base depths, drainage design, and installation standards for Cheshire patios, see our Patio & Paving in Cheshire guide. For porcelain-specific installation detail, see our Porcelain Paving in Cheshire guide.